Stefanie’s Story: Where It All Started

📍Stef in Nusa Tenggara

It may seem an obvious choice to feature Shark Allies’ Executive Director and Founder, Stefanie Brendl, in the first Shark Cafe Conservation Spotlight. As her second-in-command and mentee, I know Stefanie’s story needs to be told – and that its daring and unique twists have served as rich inspiration for my own growth as a young conservationist. I hope stepping into the mind of a leader, and some of the workings behind Shark Allies, serves you in your own conservation journey. Stefanie’s origins may differ from your own, but her spirit of making a real difference is universal.

Growing up in a small town in the German countryside, Stefanie longed to be near the ocean. Far from home or a reality, it seemed like an endless daydream and nothing more. But, in 1987 she decided to move to Guam and make it her unlikely home for a decade. As Stef describes it, she stepped off the plane, and dove right into the ocean to start her career as a diver: “The moment I put scuba gear on and went down for the very first time, I knew. Growing up in Germany, I could have never imagined that… sure you see [divers] in pictures and in films, but you never imagine yourself being that person. To me that was adventure: the wild with no limits.” In a time where Palau felt like literal unchartered waters and each dive was an exploratory one, everyone around Stef buzzed with the same sense of wonder and awe. Stefanie enmeshed herself in a crew of divers and photographers who nurtured her passion for filmmaking. She landed gigs with local dive shops, newspapers, magazines and a television show by the name of Aqua Quest.

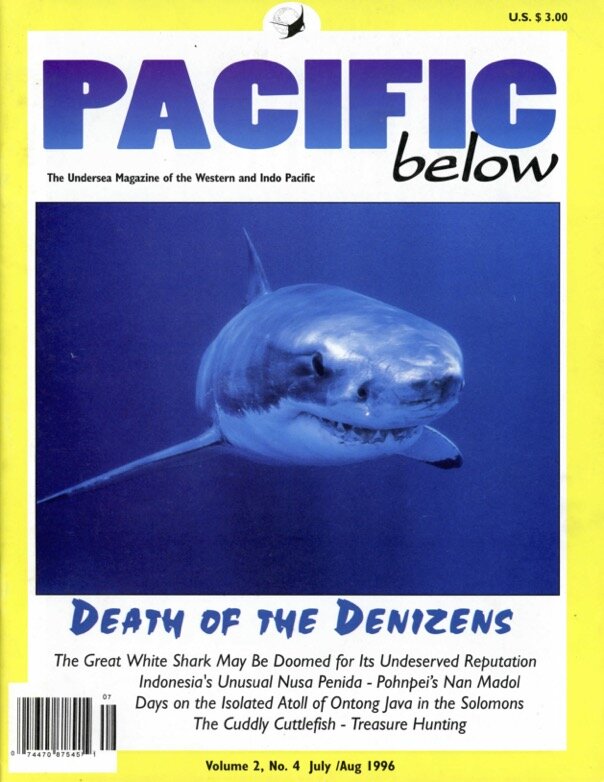

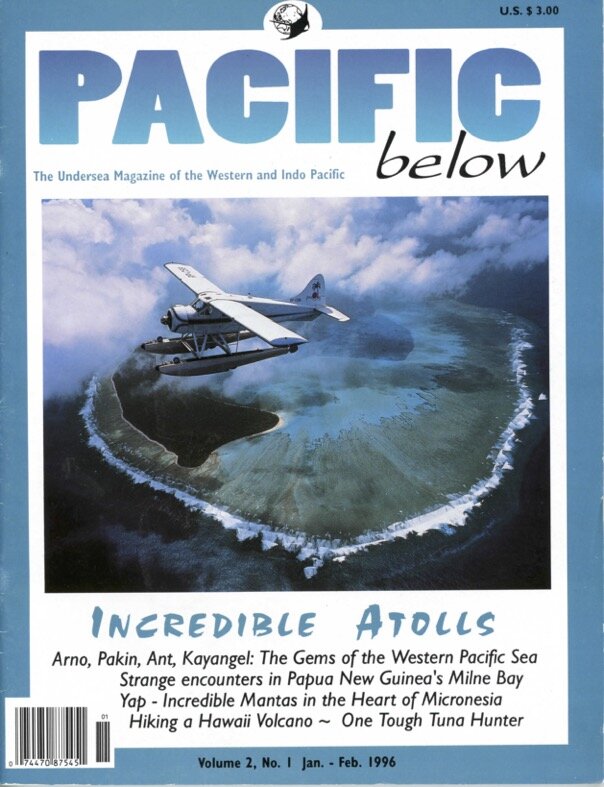

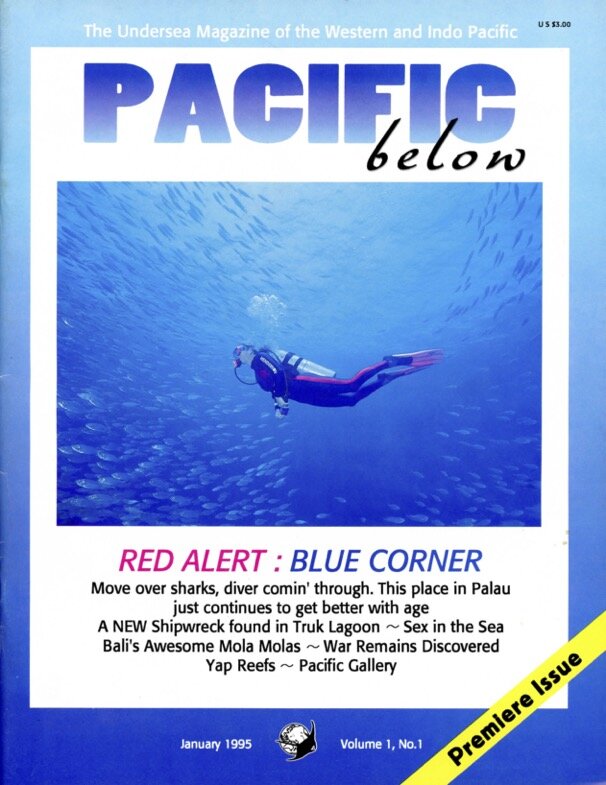

Stefanie’s early career as an underwater camerawoman and professional diver is a hefty story in and of itself, but what sticks with me most is what she did on the side to cement her passion. Underwater operating is an immense challenge, in addition to shooting on film, but her mind didn’t settle with that. Stefanie has a knack for finding holes in a market: something many preach, but can’t teach, in business school. Out of nothing, she shaped Gaia Creations, a sustainable goods company for the tourists of her island, making trinkets like postcards out of recycled papers and bowls from coconuts. It was a roaring success. I can hear Stefanie’s refrain now: “You just have to start and it will work itself out,” a philosophy that clearly comes from personal experience. Soon after she launched Gaia, her dear friend and seasoned journalist, Tim Rock, came up with the idea to create the region’s first dive magazine: Pacific Below. “Like with anything, if people see that you’re really trying your best, and that you are passionate, they will take an interest to incorporate you or help you.” As she describes it, she was “unqualified, but the only one doing it,” and thus saw success for a second time. Pacific Below allowed Tim and Stefanie to satiate their appetite for exploratory diving and underwater photography. They quickly expanded to Indonesia, notably Lembongan and Nusa Penida, and jumped on any boat they could to Tenggara and Komodo. Then, Stefanie viewed success as ambition, and ambition to her meant, “where’s the next dive trip?”

During the Christmas of 1997, after romping around the waters of South East Asia for ten years, her time in Guam came to an abrupt halt. A typhoon by the name of ‘Paka’ wiped out the whole island, taking the business of Pacific Below and her livelihood with it. Stefanie took it as her cue to move on to Bali, where she serendipitously met her partner, Jimmy Hall (I’ll save their love story for another time). Together, they found a new niche outside of sailing and diving: paragliding. Taking what she learned from Pacific Below and applying it to their new hobby, Stefanie and Jimmy pioneered this market. They were the firsts to create paragliding camera rigs, fly tandem to “get the shot”, land hundreds of never-before-seen angles…the list goes on. Around this time the North Shore of Oahu quickly became a new home for the couple, a place to clean up between adventures and make a couple bucks driving tugboats and training horses. It should come as no surprise that once Stefanie and Jimmy settled on Oahu, they sniffed out yet another gap in an industry they loved: shark diving. To them, it was simple. First, find the sharks, second, build a shark cage and third, see who wants to come out. Inspired from both a trip to South Africa and swimming through crab traps at home, they invented a thriving business. Hawaii hadn’t seen a shark cage yet, and their business served as foundation for at least seven operators in the area today.

Wrestling success for a fourth time didn’t give Stefanie the green light to kick her feet up, though. As you can already tell, that’s just not her style. Instead, she was restless, having already conquered shark diving, photography, paragliding and magazine publishing, and a new challenge was imminent. What came next wasn’t an intentional move but instead a fated start to the Stefanie Brendl we all know today: shark conservation. Tensions were mounting between fishermen and shark divers in Hawaii, a story that unfortunately cycles time and time again across the globe. As she caught wind that her company, Hawaii Shark Encounters, could be in serious trouble via bills introduced to the state legislature, Stefanie was forced to trade in her wetsuit for a pantsuit (sorry, I had to). Her hands were tied; it was either lose shark diving in Hawaii or step up to save her industry by learning the ways of lobbyists. Her definition of ambition had quickly shifted. Stefanie explains that, “usually when you think of ambition, you think of a career. But when I think about how driven I am when I want something, and the tenacity to stick it out when it sucks. You can’t do that for something that you’re not passionate about.”

Feeling like a literal fish out of water, Stefanie dedicated every waking minute to understanding her new world of policy making. In the midst of this stress and chaos, a new kind of bill emerged that caught her eye: Senator Clayton Hee’s shark fin trade ban. Senator Hee was famous for introducing at least one piece of animal advocacy legislation each year, and in 2010 it was time to address finning. The only advocates that showed up to this bill’s first hearing were unsurprisingly The Humane Society of the United States and Stefanie. After the committee hearing, Senator Hee’s team ran after Stef. Her mind immediately jumping to the notion that she was in trouble for her testimony, perhaps they saw her as a tour operator with an ulterior motive? Not quite. Instead, Hee asked her for help, noticing that she clearly knew how to show up, persuade and fight. “It seems like you have something to say.” That hearing changed the course of Stefanie’s life. From then on, she reported to Senator Hee’s office every single morning, “Where do you need me, who do I need to talk to today?” He shaped her confidence in giving sharks a voice, walking the halls of the legislature and knocking on the opposition’s door. By then, she wasn’t embarrassed to pick up the phone and call WildAid and Shark Savers to join in. Yet again, Stefanie perfectly placed herself in the middle of an intimidatingly new space. The glitter of a challenge was irresistible. “You conquer it not because you have the tools, but by sheer perseverance at the time,” she tells me.

Since you’re still with me, I tell you all of this not because Stefanie’s story is a clear-cut formula for a successful career as a conservationist, but because a perfect storm of events held a strong woman at its center, standing tall and true to herself, no matter who was behind or in front. Stefanie approaches protecting sharks the same way she approached photography and diving in her early days. And when I say early days, I mean those when you would bring 4 film cameras down with you and plop them in the sand to give you 144 chances at the perfect shot - you deal with limitations by preparing until you can’t prepare any more, leaving no stone unturned. To Stefanie, prep is Zen, and the work isn’t worthwhile unless there’s a mission to be had in foreign territory. Her main artery pulses compassion and motivation in the face of a challenge, and serves as the core of Shark Allies. She has taught me that it’s all the more appealing if the challenge before us seems impossible. Look at the Florida campaign - everyone gave us a firm pat on the back and a crooked smirk like, “good luck, you’re both nuts,” because it had already failed twice. Instead of taking their word and bailing behind them, Stefanie fearlessly lead us to success.

We are always thinking about how to improve Shark Allies, how to help more animals and bring more advocates along the way. That’s how Shark Cafe was born. We can’t wait to see what it evolves into and who it inspires in its wake! Stef empowers me when the unchartered waters seem too rough, “The stuff worth doing, you never know if it’s going to work. Most things I’ve done were worth pursuing just to make a bit of a difference, even if it was more likely to flop. It’s worth pursuing just to see how far we can get. Just start and you’ll figure it out.” So, what are you waiting for? Just start. And with that, a couple words of wisdom from ‘The Oracle’ herself…

LI: What do you think 20 year old, fresh off the plane in Palau, Stefanie would think of where you are today? Are you where you thought you would be? What would Stefanie then, be most proud of you for now?

SB: I think 20 year old Stef could have never imagined where this path leads and I didn't really think about where I would end up decades later. I was just discovering the underwater world and trying to learn the basics. All I wanted to do was see the world and find a way to make that my job. I admired people that were working in conservation and exploration. I think Stefanie then would be most proud of the fact that I kept moving and evolving and that I am now actually not just adventuring around but actually making an impact. And that I developed the confidence to blaze my own trail.

LI: Flipping it, if you could give advice to yourself, circa your first dive under water, what would it be?

SB: I would say, “This is it.” Don't question it and don't let anyone stop you from doing exactly what you want to do. I had some people in my life that had their own ideas of what I should be and what I should not do. It seems I had to fight that almost all my life. Good thing my desire always made me stubborn enough to carve out my own space.

LI: Lately, there has been a frenzy of hopeful progress for sharks, yet perpetual pressures seize to exist, sparking concerning new studies on population decline and industries that won’t back down. In your opinion, how can we best protect sharks in the next 10 years? Where should our priorities lie?

SB: The movement to protect sharks has grown, and the general attitude about sharks has gotten a lot better in the last 15 years. We have to use that momentum to tackle the same issues but multiply our effect to achieve change on a much broader level. I am encouraged by the continued success of fin bans. However, I do fear that we are winning battles but losing the war right now. Many in the conservation community feel the same way. Shark conservation needs to be lifted out of obscurity so it will be recognized as an urgent issue and treated that way. So far, sharks have mostly been dealt with as a niche cause, powered by grassroots groups and small-time non-profits. But this will not be enough. The major issues that need to be addressed are…

Overfishing: Too many sharks are taken every single year. There isn't much arguing that point. Even by those that favor the sustainable fishing of sharks. The main drivers of overfishing are the demand for shark fins and the massive bycatch rate in fisheries. Bycatch of sharks could be much better addressed if there weren't so many excuses to keep "accidentally caught" sharks. Squalene, meat, souvenirs... everything made from sharks that can be sold encourages the targeting of sharks.

Lack of protection: We have to get sharks on protected species lists and make sure those determinations are respected and enforced. We also have to create protected areas where they are not fished at all, whether that is via shark sanctuaries or full Marine Protected Areas.

Bring recognition to the true value of sharks: Sharks have a much greater economic value alive vs dead. Industries such as eco-tourism, film, and media make billions off live sharks. The ecosystem services sharks provide, year after year, would be in the billions if calculated properly. After all, what is the value of keeping fish populations healthy, the ocean clean, and the systems thriving?

Raising the profile of shark conservation: The community really needs to pull together to level up the efforts. Big international treaties and agreements are at the forefront of the world's mind, due to climate change and the fact that people finally recognize it's existence. However, Life in the ocean always seems to get a disproportionately small amount of attention. If we want sharks to have a chance, we have to make sure they are part of the discussion. And not just under the broad category of sustainable fisheries, which is where all shark negotiations usually end up.